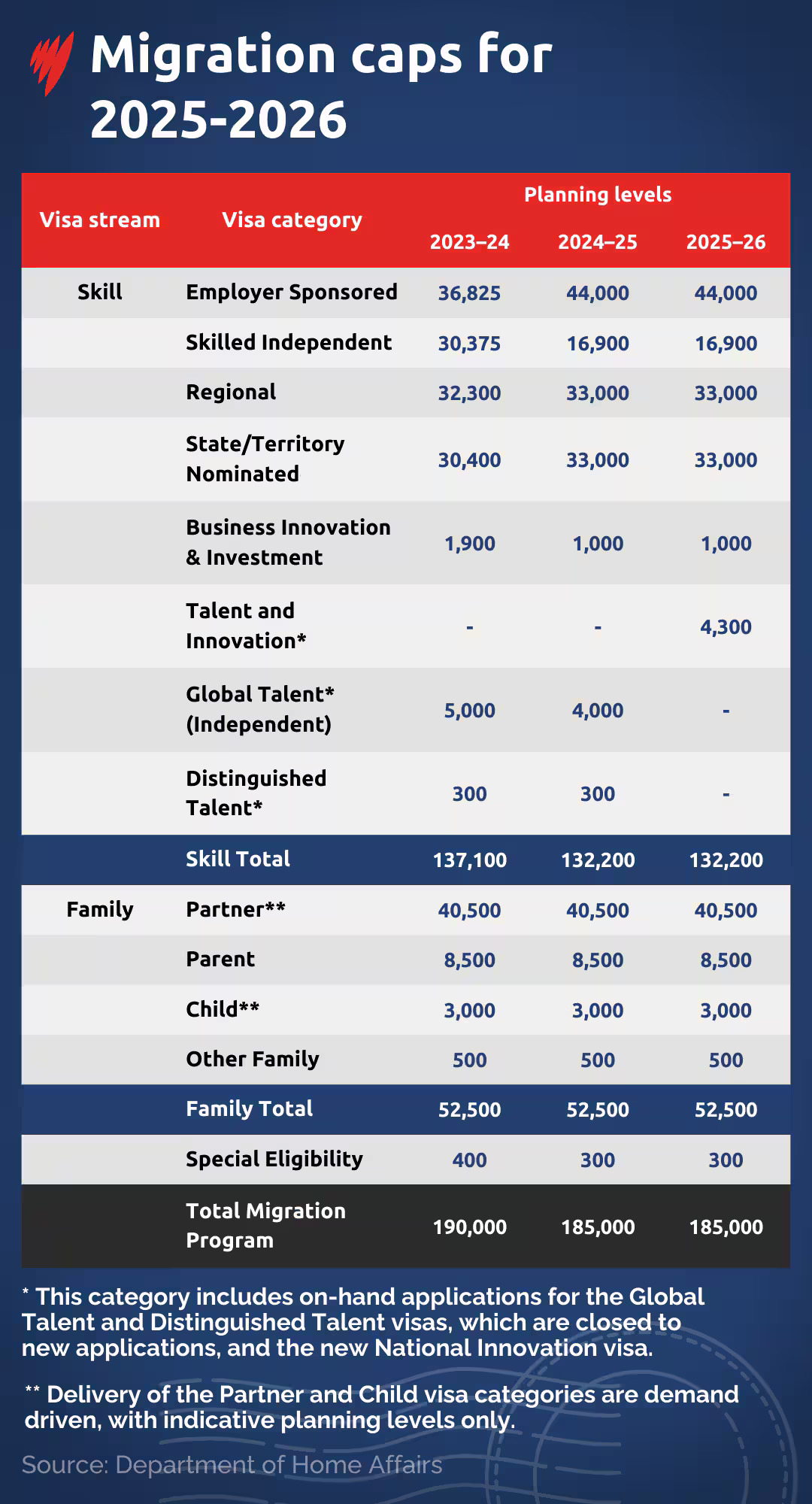

For 2025–26, Australia’s permanent migration program remains at 185,000 places, unchanged from the previous year, with continued emphasis on skilled migration.

A total of 132,200 places (around 71 per cent) are allocated to the skilled stream, while 52,500 places (approximately 28 per cent) are allocated to the family stream, predominantly partner visas.

The government says the allocation aims to boost Australia’s productive capacity and address workforce shortages, particularly in regional areas.

But Adelaide-based migration agent Mark Glazbrook said the system still faces deep structural challenges.

He warns the success of the skilled stream depends not just on who is selected but on how effectively their skills are used once they arrive.

“If skilled migrants come to Australia to work as mechanics or in construction, for example, but they lack the competency and proficiency that local businesses need, not only is the migrant more likely to be underutilised, they still need to live in a house — but another migrant will need to come to fill the job the first couldn’t do,” he said.

Meanwhile, settlement patterns show little sign of shifting.

Despite regional visa allocations, most new arrivals continue to settle in Melbourne, Sydney, and, increasingly, Brisbane and Perth — a trend Glazbook said highlights the gap between policy intentions and real-world outcomes.

International student intake climbs — but with tougher scrutiny

After two years of attempts to rein in student numbers, the Albanese government will adopt a more moderate stance in 2026. The target intake will rise from 270,000 in 2025 to 295,000 in 2026, even as stricter visa checks remain in place.

Skills and Training Minister Andrew Giles said in August: “The settings that government has put in place for 2026 will ensure that the international VET [Vocational Education and Training] sector can grow sustainably to better meet skills needs, in Australia and the region.”

As part of the reforms, universities seeking an increase to their allocation will need to demonstrate stronger engagement with Southeast Asia and make progress in providing secure student accommodation for both local and international students.

Phil Honeywood, CEO of the International Education Association of Australia, encouraged the pivot to closer neighbours such as Thailand and Indonesia, but expressed concerns about housing backlogs.

“It’s taking purpose-built student accommodation companies anything up to three years to get a project approved and commence construction. So it’s a long game,” he told SBS News in August.

Priority processing will continue for Pacific and Timor-Leste students and government-funded scholarship holders.

From 2026, Australian-schooled international students and those coming through TAFE or recognised pathway providers into public universities will be exempt from the government’s National Planning Level, or cap. Longer-term changes are also on the way, with a new Tertiary Education Commission expected to oversee student caps and university allocations from 2027.

But Abul Rizvi, a former deputy secretary at the Department of Immigration from the early 1990s to 2007, said the system is still adjusting unevenly.

He noted that the planning levels have created very different outcomes across sectors.

“Private higher education providers had by September significantly exceeded their planning levels. VET and public universities were well below their planning levels,” he told SBS News.

Rizvi said public universities are now heavily reliant on rapid visa processing to meet next year’s allocations.

“There was a big increase in offshore student applications for higher education in September 2025 … Public universities will be relying on those applications being processed quickly and the students arriving quickly to get near their allocations,” he said.